Antifa Means Antifascist

Issue 1: Well behaved women

January 2026

Antifa Means Antifascist issue 1

Pre-orders available now. Available for $8 (zine only), or $20 with a set of 10 stickers from the contents.

Issue 1: “Well-behaved women”

We first came across the slogan “Well behaved women seldom make history” on bumper stickers back in the 80s. We took it as a reminder to break the rules and push boundaries in order to make a change, to “make history”. While its origin is more nuanced, the slogan fits the aim of our project on several levels.

Laurel Thatcher Ulricht coined the phrase to explain why she chose to focus on the “quiet” “respectable” women in conservative communities: because otherwise they’d be ignored by history, their contributions unseen. But she also welcomed the popular appropriation of this phrase as encouragement to rebel, and she didn’t see a contradiction between the two meanings.

As those of us resisting fascism today work to reclaim the initiative, we need more rule-breakers who can disrupt the narrative and make our own history. At the same time, we need to recognize the work being done by people who don’t making the news, the caregiving and kin-keeping work that hold people together through the dark times.

This project, then, is an attempt to bring the two threads together. We honor five women who did make history by refusing to collude in their own oppression. We also want to highlight examples of everyday antifascism which are being done by people who aren’t on the front lines and might never be the subject of history.

it’s no mystery

— Linton Kwesi Johnson

we’re making history

Sophie Scholl

Sophie Scholl’s story offers a powerful example of principled everyday antifascism. From a mainstream middle class German family, she was even an enthusiastic member of the Hitler Youth in her teen years. When she was 16, her older brother Hans was arrested under the Nazi law criminalizing homosexuality. Watching someone she loved be criminalized and imprisoned for who he was may have been one of the first cracks in her faith.

Looking around, she began to notice parallels between the repression of her brother and other queer friends with the struggles of all the other groups targeted by the Nazis.She grew more and more disillusioned with the cruelty and lies of the system, and within five years had become a committed anti-Nazi activist. She joined a group (called “The White Rose”, after a novel by the anarchist B. Traven) focused on writing and distributing resistance propaganda, often at great personal risk.

While there were numerous other organized antifascist movements, this group stands out in that it was completely self-organized. Sophie, Hans, and the other rebels who worked with them were just young people from the Nazis’ core demographic, tirelessly explaining to others like themselves why resistance was not only possible but necessary.

“We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace!”

– White Rose Leaflet #4

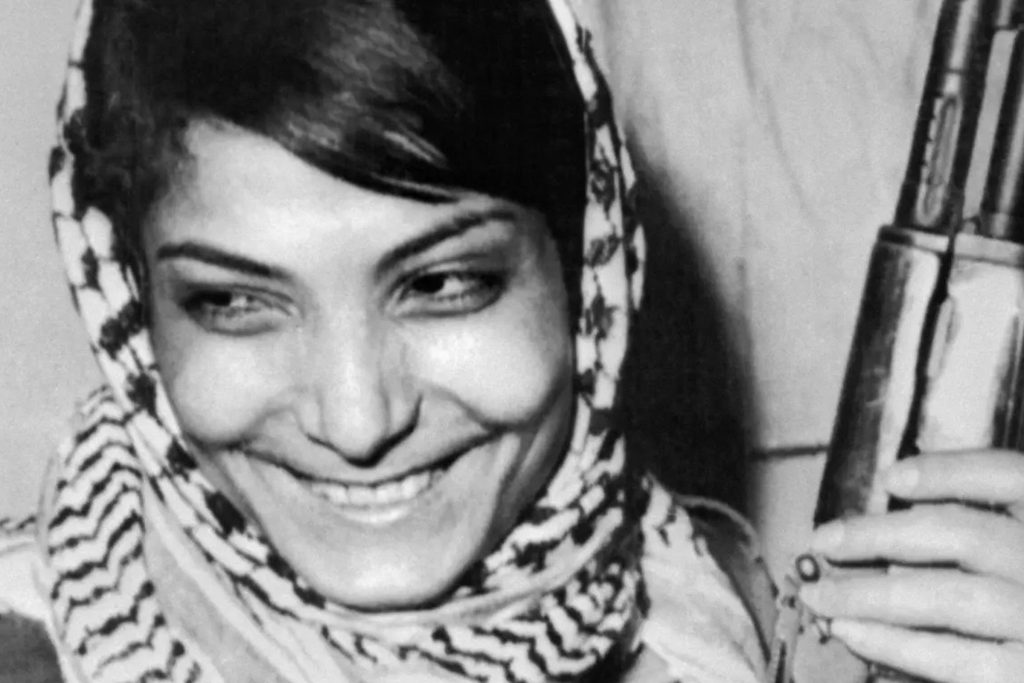

Leila Khaled

Palestinian women have participated in all forms of resistance, including armed resistance, for as long as the Palestinian people have fought for national liberation. Leila Khaled is the most well-known of these heroic women. She has dedicated her life to free Palestine from colonial occupation and to the international struggle for socialism.

Born in 1944 to a middle-class Palestinian family in Haifa, she was only four years old when her family was dispossessed in the Nakba. She left her comfortable home and the café her father had owned for over 20 years to a Lebanese refugee camp.

Growing up poor and displaced, she developed political consciousness young. By the time she was 15, Leila was a dedicated activist with the student movement and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. She joined the PFLP’s armed wing and took part in two high-profile airplane hijackings in 1969-70. On the first hijacking, she directed the pilot to fly over her home town of Haifa, which she had been unable to visit since childhood.

While she was world-famous as the subject of an iconic photo, an attractive young woman with a kaffiyeh and an AK-47, she was never a two-dimensional figure. After retiring from armed actions, she continued her work organizing to raise the question of the right of displaced Palestinians to return to their homeland.

“Our minimum objective was the inscription of the name of Palestine on the mind of every self-respecting libertarian who believes in self determination.”

Assata Shakur

Born in 1947, Assata Shakur grew up between North Carolina and New York, experiencing the different forms of racism on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line. She went to college for business, but found revolutionary consciousness instead. She met activists from around the world, and from her first arrest protesting the lack of black faculty, she continually threw herself deeper into struggle, looking to find where she could serve the community.

She ended up joining the Black Liberation Army, an offshoot of the Black Panther Party inspired by guerilla warfare in places like Vietnam, Algeria, and Cuba. They mounted a campaign of guerilla activities against the U.S. government, using such tactics as planting bombs, holding up banks, and murdering drug dealers and police.

Assata spent the early 1970’s in and out of jail, on trial for a number of armed actions carried out by the Black Liberation Army. She beat these charges for years, but eventually she was captured in a shootout where a state trooper died. She was shot twice while surrendering, and this time she was finally convicted.

She gave birth while on trial and was sentenced to life plus 30 years. She understood the trauma her child experienced growing up motherless to the generational trauma of countless black families broken apart by white supremacy and began planning her escape.

In 1979, she was liberated by a group of Black Liberation Army fighters supported by a coalition of other underground organizations. Public support was massive, shown by “Assata is welcome here” posters all across the country. She remained in hiding for five years before resurfacing in Cuba and applying for asylum.

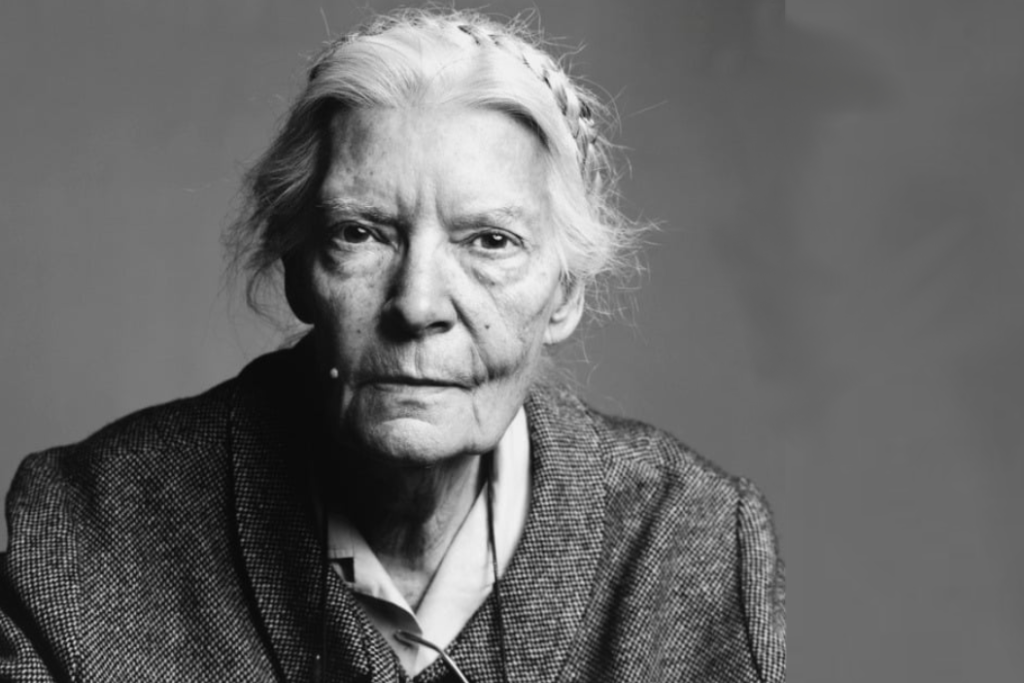

Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day, a founder of the Catholic Worker movement, was a great example of quiet and unglamorous service to the poor and to the cause of social justice. She described her goal as to “bring about the kind of society where it is easier to be good”, and in truth she thought deeply her whole life both about building a just society and about being good.

As a child, she was drawn to religion, getting deeply into the rituals and scriptures of her neighborhood church despite non-religious parents. In her teens, she also developed a deep lasting interest in social justice and read extensively in socialist and anarchist thought. She moved to New York to work as a journalist for several socialist papers. She organized for radical causes and lived a free-spirited unrestrained life.

She was committed to seeing the full humanity in people, even as they were suffering or sinning. She took the people seriously enough that later she later converted to the religion they shared. She brought this sense of the dignity of the poor to the movement she founded, and emphasized voluntary poverty and precarity.

Catholic Workers helped people the way they needed. This included mutual aid centers providing shelter, shared meals, and culture; as well as farming communes. Dorothy often cited the IWW slogan that we are “building a new society in the shell of the old.”

“To feed, clothe, and shelter the hungry and harborless without also trying to change the social order so people can feed, clothe and shelter themselves, is to show a lack of faith in one’s fellows as heirs of heaven”

Greta Thumberg

“The children are our future” is a common trope: relying on the naive idealism of youth to paper over the worst brutality of modern capitalism. But in reality, the young people who do speak up end up being ignored, trivialized, and co-opted. Greta Thunberg is a modern example of a young person who has successfully resisted this recuperation.

Greta, as the legend goes, was once a child like most of us. After learning about climate change, she became profoundly depressed and she stopped speaking for years. What could a ten-year do to stop the apocalypse? In 2018, she began a “school strike”, standing alone outside parliament with a handmade protest sign. Eventually 20,000 students joined these actions. While her public face got her invited to speak at parliament and the UN, she found herself mocked and dismissed as an unrealistic child who couldn’t possibly have any real solutions.

It would have been seamless for Greta to become a harmless “pet critic”, making empty critiques that never challenged power relations. Instead, she has continually spoken out about the connections between the environment and the systems of capitalism and imperialism. And she’s consistently made alliances with people fighting against exploitation, colonization, and genocide, from America to India to Palestine.

We can no longer let the people in power decide what is politically possible. We can no longer let the people in power decide what hope is. Hope is not passive. Hope is telling the truth. Hope is taking action. And hope always comes from the people.